In discussions of the greatest American filmmakers of all-time, the name Martin Scorsese is guaranteed to turn up. Since making his directorial breakthrough with Mean Streets some 50 years ago, the man they call Marty has – alongside a troupe of reliable collaborators both behind and in front of the camera – contributed more bona-fide masterpieces to the cinematic canon than most other filmmakers you could name. And he’s done so whilst continually reinventing himself, honing his own craft whilst supporting and advocating for the cinematic experience and its preservation all over the world.

With Scorsese’s latest work, Killers Of The Flower Moon, once again reminding us of his filmmaking power, Team Empire gathered together to rank the master’s works. From taxi drivers to good fellas, the son of God to the wolf of Wall Street, kings of comedy to morally-fraught missionaries, and many more, there’s a Marty for all seasons in this rarified bunch of cinematic gems (though, for the purpose of the list, we’re focusing on his narrative films, rather than his extensive documentary and concert feature work).

So, lovers of cinema, please join Empire as we present our ranked list of every Martin Scorsese movie. The real winner? Cinema itself.

26) Who’s That Knocking At My Door

Few films have gone through more titles than Martin Scorsese’s debut. It was variously called ‘Bring On The Dancing Girls’, ‘J.R.’ and ‘I Call First’ before it landed on Who’s That Knocking At My Door, taken from the song by The Genies. The autobiographical story is a character study of J.R. (a ridiculously young Harvey Keitel), a neighbourhood guy who loves Westerns and meets a never-named middle-class girl (Zina Bethune, just credited as Girl) who likes European art films. It’s a rough-hewn affair — Scorsese had to put in a gratuitous sex scene cut to The Doors’ ‘The End’ (years before Apocalypse Now) with a visibly-much-older Keitel to secure release — but within the scrappiness are moments of Marty magic (a party captured in slow-motion) that point to the later genius. Catholic guilt, rituals of Italian-American life, great needle-drops and infectious film buffery are all here, but they’re on a shoestring that makes Mean Streets look like Killers Of The Flower Moon.

25) Boxcar Bertha

Following up his debut, Scorsese, the ultimate New Yorker, went on the road to the American South (the film shot in Arkansas) to make this Roger Corman exploitation picture. It follows the titular orphan (Barbara Hershey) who teams up with a Union Rep turned bandit (David Carradine — think a renegade Mick Lynch) to go on a crime spree during the Depression to exact revenge on evil railroad bosses. Only his second film, there are a few Scorsese-isms on display — a strong sense of locale, no-nonsense staging of violence, a killer crucifix image — but the film’s importance in the director’s filmography lies in what it taught the fledgling filmmaker about how to put a film together on budget and schedule, and work within the studio system. Next up: Mean Streets.

24) New York, New York

Where Spielberg took until 2021 to shoot his epic ode to the golden age of the Hollywood musical with West Side Story, Scorsese tackled his much earlier in his career, straight after Taxi Driver — having squeezed his camera into an NYC cab, he was bursting to film some free-wheeling action instead. On paper, the tale of romance between sax-man Jimmy (Robert De Niro) and singer Francine (Liza Minnelli) looks promising: after all, few filmmakers can fuse music and visuals together quite like Marty. Unfortunately, it turned out to be a critical and box-office dud, driving the director to drugs and ending his ’70s hot streak. But while wobbly and filled with unmemorable improvised dialogue, there are great things to be found in the movie – not least Minnelli’s peppy performance and the now-iconic titular theme tune, borrowed by Frank Sinatra two years after New York, New York’s release. And the story’s had a recent resurrection in the form of a Broadway adaptation, which opened this April.

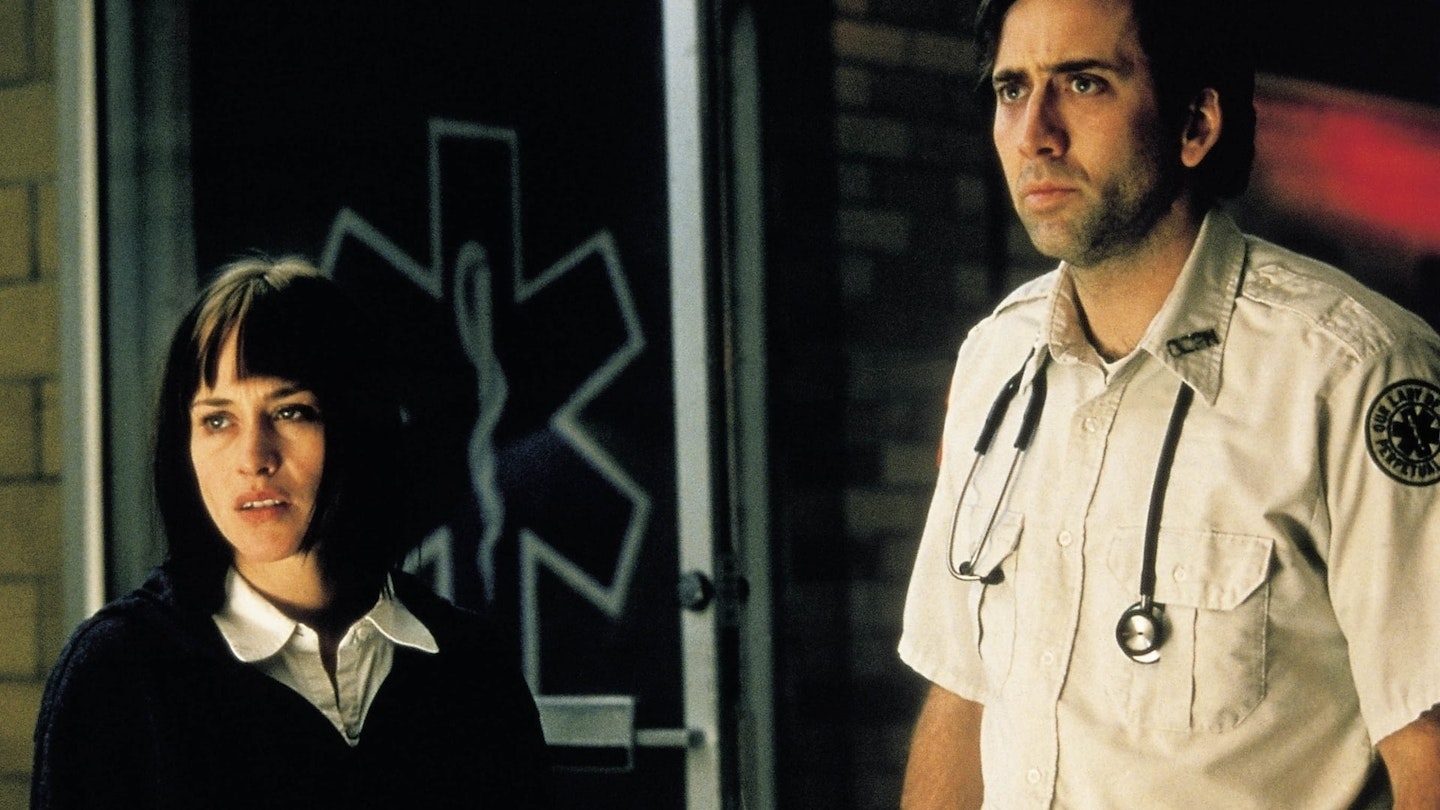

23) Bringing Out The Dead

Scorsese’s 1999 psychological drama saw the filmmaker reteam with Taxi Driver scribe Paul Schrader to once again follow a lost soul wending their way through the mean streets of New York – and while it’s lesser-known in his filmography, it’s somewhat underrated. Nicolas Cage stars as sleep-deprived, deeply depressed paramedic Frank, a man haunted all-too-literally by the ghosts of those he has failed to save. A weighty examination of grief and guilt couched in a subversive take on the drive-all-night subgenre, Marty’s adaptation of Joe Connelly’s novel remains fascinating. Robert Richardson’s ethereal, hallucinatory cinematography, Thelma Schoonmaker’s disorientating editing, deliberately blown-out, purgatorial lighting and Cage’s lead performance – restrained and restless in equal, evocative measure – add up to a tone poem of a piece that gets under the skin, exploring themes of regret that would go on to dominate later Scorsese works.

22) Gangs Of New York

You can’t fault the ambition of Gangs Of New York. For a filmmaker long concerned with gangs, New York, and American history, it’s almost inevitable that Scorsese would end up making a film about, well, rival gangs fighting for territory in 19th Century New York. The result is overly sprawling, a rare example of the masterful filmmaker’s reach somewhat exceeding his grasp, not helped by script issues and Miramax meddling from Harvey Weinstein – but for all the flaws here, it is still a thunderous work, punchy and pulpy and peppered with bombastic performances. While this was the director’s first team-up with Leonardo DiCaprio (front and centre here as vengeful youngster Amsterdam), it’s Daniel Day Lewis who looms the largest as the scenery-chewing, ludicrously-behatted Bill The Butcher – snarling and slicing and soliloquising up a storm. Today, it’s the practical filmmaking that really stands out – shot before digital techniques became the norm, Gangs plays out on truly gigantic sets with hordes of extras in a way that’s all-too-rare today. Add on a killer final shot, and you have a flawed gem.

21) Hugo

Martin Scorsese’s love of cinema is well-documented. From his World Cinema Project and founding of The Film Foundation, to his vocal advocacy for the cinematic experience and seemingly encyclopedic knowledge of the form – the guy loves moving pictures. Fitting, then, that his sole truly family-friendly work is a swooning, unapologetically sentimental love-letter to the medium, designed to be adored by young and old alike. Adapting Brian Selznick’s The Invention Of Hugo Cabret, the film follows Asa Butterfield’s titular waif who lives in the walls of the Gare Montparnasse in Paris, as he tries to solve the mystery of A Trip To The Moon filmmaker Georges Méliès’ (Ben Kingsley) abandonment of his craft. Buoyed by its stunning production design and Avatar-level-brilliant use of 3D, Scorsese’s tribute to the founding fathers of film and the connective, imaginative power of cinema is spellbinding.

20) The Aviator

The second collaboration between Scorsese and Leonardo DiCaprio doubles down on one of the director's favourite themes: people pushed by driving ambition to pull off incredible feats, albeit with a terrible personal price. Scorsese could clearly empathise with Howard Hughes' driven desire to make movies and excel in aviation, while Leonardo DiCaprio threw himself into research to capture the business titan's personal struggles with OCD. It's a sweeping, lush movie full of incident and careful detail, with superb work from the leading pair, plus the likes of Ian Holm, John C. Reilly, Alec Baldwin, Jude Law and Willem Dafoe. The reward was an 11-strong haul of Academy Award nominations, from which it took home five (including Best Supporting Actress for Cate Blanchett, in an excellent turn as Katharine Hepburn).

19) Shutter Island

Whilst Scorsese’s filmography includes plenty of chilling moments, 2010’s Dennis Lehane adaptation Shutter Island remains the closest he’s ever gotten to making an out-and-out horror. With its creepy asylum setting, dank lighting, heightened sound design, and claustrophobic camerawork, the film looks and moves like a gothic chiller. But the real horror comes as we watch U.S. Marshal Teddy Daniels – played with extraordinary interiority by a transformative Leonardo DiCaprio – mentally come undone. What begins as a compelling but unremarkable mystery, with Daniels investigating the disappearance of a missing woman at an isolated psychiatric facility, soon becomes a pure psychological horror, with haunting visions and inexplicable goings-on leaving our man Teddy questioning his sanity. It’s not until the film’s twist ending however – an expertly-directed and -acted rug-pull – that it elevates a possibly obvious reveal into something crushingly tragic.

18) The Last Temptation Of Christ

The Last Temptation is Scorsese’s biggest passion project, one that collapsed multiple times and was ultimately vilified on release by Christian religious groups who picketed outside cinemas over its departure from the Gospels. Based on Nikos Kazantzakis’ novel, this serious, heartfelt film explores the none-more-Scorsese idea of Christ (Willem Dafoe) caught between his divinity and his mortal side (doubt, depression, lust — the usual human stuff). Dafoe eschews previous beatific portrayals of Christ by being engaged and warm, while Scorsese’s filmmaking, from Michael Balhaus’ whirling camera to Peter Gabriel’s driving world-music score, is eons away from the typical Biblical epic. There’s Harvey Keitel as a wise-acre Judas Iscariot and David Bowie as a bizarre Pontius Pilate. But, its final moments, when Christ – having resisted all temptations – finds himself on the cross and shouts, “It is accomplished!”, are profoundly moving, whatever your spiritual beliefs.

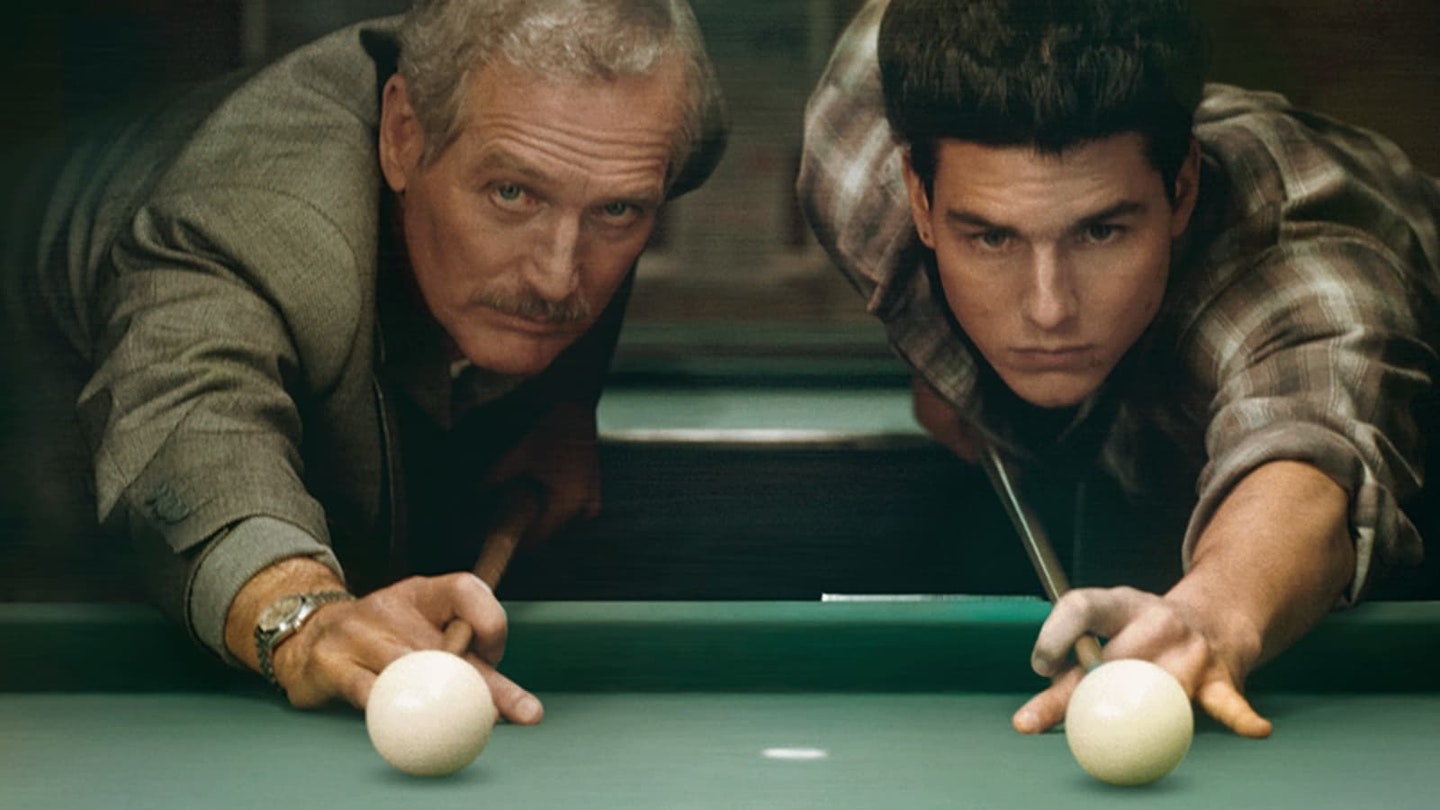

17) The Color Of Money

Martin Scorsese is not in the franchise business – he's never made a sequel to one of his own movies, preferring to stride on to the next subject each time. Yet he was drawn to follow up someone else's film, in this case Robert Rossen's 1961 pool drama The Hustler. You can see the appeal: Paul Newman reprising his role as legendary cue-slinger Fast Eddie Felson opposite one of the big rising stars of the time, Tom Cruise, whose pool hustler Vincent Lauria (so egotistical he has VINCE emblazoned on his own shirt) threatens to derail their money-making scheme by refusing to rein in his ball-in-pocket prowess. Newman took the chance to return to one of his best roles and won an Oscar for his performance. Cruise, meanwhile, showed his versatility and, in a foreshadowing of his Mission: Impossible ways, pushed to do his own trick shots. Effortlessly cool and stylish, this is Scorsese feeling frisky, and delivering a commercial hit.

16) Cape Fear

It’s not often that Scorsese enters schlocky, vaguely-gothic thriller mode, but whenever he does it’s a treat. Decades before Shutter Island, he went there with this remake of the Gregory Peck-starring 1962 film, following up GoodFellas with something else entirely. Robert De Niro is tatted up and wild-eyed as Max Cady, released from prison after an extensive stint before seeking revenge on his lawyer Sam Bowden (Nick Nolte) and family. Choking down vast lungfuls of cigar smoke, inveigling his way into young Dani’s (Juliette Lewis) school, and demonstrating seriously bad cinema etiquette, the psychopathic Cady looms over the Bowdens, threatening to drive Sam over the edge – quite literally, in its finale on a boat in a raging river. Richly atmospheric – all broiling skies and the promise of violence – and performed with cackling intensity by De Niro in particular, this is a pure blast of popcorn Scorsese. The only way it could be better? If it closed with an extended Max Cady-stepping-on-several-rakes gag.

15) Silence

Scorsese grew up an altar boy – and while he wrestled with his faith in The Last Temptation Of Christ, he returned to the subject later in his career with this adaptation of Shūsaku Endō’s novel. Set in 1600s Japan – a time in which Christians were hunted down, tortured and murdered – it stars Andrew Garfield and Adam Driver as Jesuit priests Sebastião Rodrigues and Francisco Garupe, respectively, who venture East when they learn that Liam Neeson’s devout Cristóvão Ferreira has apparently recanted his faith over there. What follows is an often brutal Conrad-esque odyssey as Rodrigues and Garupe seek out their missing mentor – an elemental film where every sea spray, every breeze, every muddy splatter feels tactile. As Rodrigues sees violence against Christians play out all around him, he increasingly feels that he hears nothing from God – only silence. It’s a long, dark, serious watch that occasionally overplays its hand when it comes to some religious visions – but it’s incredibly powerful, and surprisingly gripping for its not-inconsiderable runtime.

14) The Departed

People have a lot of negative things to say about remakes, and there are many dodgy examples of re-worked classics. But Scorsese proves that it can work to Oscar-winning effect with this overhaul of Hong Kong crime thriller Infernal Affairs – still his only Best Picture and Best Director win. Switching the action to the dark underbelly of Boston, Scorsese and writer William Monahan strike gold with the criss-crossing story of an undercover cop in an Irish gang (Leonardo DiCaprio’s Billy Costigan) and a mole from said gang in the police department (Matt Damon’s Sullivan) looking to ferret each other out. It’s a knotty and propulsive ride, with DiCaprio and Damon diving deep into the twisted psychology of their yin-and-yang characters – though it’s not quite top-tier Scorsese crime flick, nearly unbalanced by Jack Nicholson’s wild turn as mobster Frank Costello. By anyone else’s standards, this would be a masterpiece – bolstered by Mark Wahlberg swearing up a storm as confrontational cop Dignam, and Vera Farmiga bringing heart as Billy’s psychologist Madolyn. Strike up the bagpipes.

13) Kundun

Criminally one of Scorsese’s lesser loved films, Kundun is a sublime experience – a religious journey that feels genuinely spiritual, thanks to a purity of vision and a truly transcendental, hypnotic score by Philip Glass. Written by E.T.’s Melissa Mathison, telling the story of the Dalai Lama, Scorsese leads us through Tibet with dreamlike wonder, his own version of a sand mandala. As tense as it is serene, chronicling the discovery, tutelage, escape and exile of the country’s ceaselessly stoic leader, it’s as much in thrall to the land as it is the man, basking in the beauty of it all while unafraid to have its dreams turn to nightmares when it needs to. If you haven’t seen it, do yourself a favour and submit to its charms. It’s an enveloping, rewarding watch.

12) After Hours

Scorsese bounced back from the box office disappointment of King Of Comedy with this curious small-scale black comedy, that crossed his desk courtesy of producer pair Griffin Dunne (who would go on to star in the film) and Amy Robinson (who starred in Mean Streets). Set against a chaotic night in the SoHo neighbourhood of Scorsese’s beloved New York City, the film follows Dunne’s aimless computer data entry worker Paul down an urban rabbit hole where he meets all manner of villains, outcasts and oddballs. It’s a rare but riveting collaboration between the filmmaker and Dunne, bolstered by excellent character performances from Catherine O’Hara, Linda Fiorentino, Teri Garr, and John Heard. This may not be Scorsese’s bread and butter, but it's a kinetic, brashly funny curveball nonetheless.

11) The Age Of Innocence

Scorsese’s lifelong fascination with his hometown extended to its history. In Gangs Of New York, he looked at the parallels of modern criminal life with the city’s violent early years; in The Age Of Innocence, he looked at a different strata of Manhattan society, while still exploring his most beloved recurring themes — the codes and rituals of a tight-knit community; the toxic pressures of masculinity; the cameo from Scorsese’s mum, Catherine. Effectively the director’s take on a Merchant Ivory picture, it’s a sumptuous look at Victorian repression, with stunningly understated performances from Daniel Day-Lewis and Michelle Pfeiffer, whose deep passion for each other rumbles beneath tight grimaces and even tighter corsets. There aren’t many costume dramas on Scorsese’s Scor-CV, but on this evidence, maybe there should be?

10) Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore

Before Travis Bickle and Jake LaMotta, Rupert Pupkin and Jimmy Conway came Alice Hyatt, Ellen Burstyn’s wayward widow. Burstyn, seeking out a grounded, realistic woman’s story while in the midst of filming The Exorcist, requested a young Scorsese to direct Alice upon Francis Ford Coppola’s recommendation. It proved a stellar choice. The film follows Alice as she makes a tumultuous journey across America following her husband's sudden death, with the hope of making it as a singer. Scorsese’s energy – fresh off the back of Mean Streets – imbues Alice’s journey of self-discovery, which sees her reckoning with her mistakes while trying to create a better life for her young son, with grit, vitality and a palpable love for her character. It’s a beautifully-observed and empathetic portrait, playing to Scorese’s unique ability to capture American realism even in his early career.

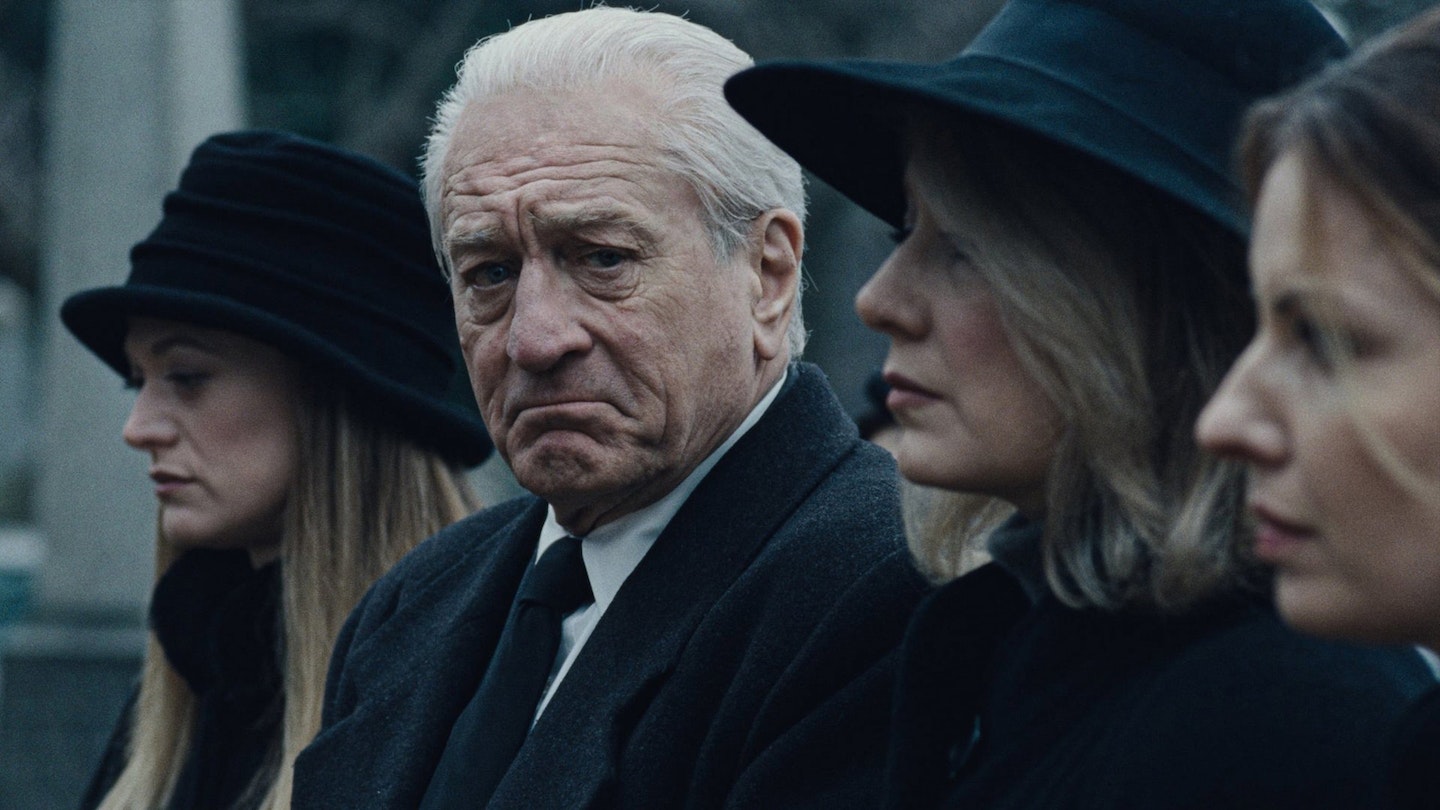

9) The Irishman

The Irishman is to the mob movie what Unforgiven was to the Western – a jaw-slackening reckoning with a history of violence, made by a man whose work in the genre has defined the form. Here, Scorsese assembles an all-star cast (DeNiro! Pesci! Pacino! Graham!), all on mercurial form to tell the story of Frank Sheeran (DeNiro), the war-veteran-turned-mob-enforcer who rose through the ranks of the Bufalino crime family, befriending and then allegedly killing Teamster President Jimmy Hoffa (Pacino). Utilising cutting-edge de-ageing tech, the film is an epic, decades-spanning yarn every bit as blood-spattered, double-cross-filled, and immersed in the world of organised crime as Goodfellas or Casino. But there’s a quietude to The Irishman, a mortal awareness that looms over the picture – punctuated by on-screen text introducing characters by their date and cause of death – that is profoundly moving. And that final hour? “Don’t shut the door all the way.” Haunting isn’t even the word.

8) Killers Of The Flower Moon

Talk about a late-career masterpiece. Killers Of The Flower Moon tells the horrifying true story of the Osage murders in 1920s Oklahoma during ‘The Reign Of Terror’, Scorsese wrestling with his nation’s bloody history – and his own cinematic legacy. The film follows Ernest Burkhart (Leonardo DiCaprio), a morally invertebrate war veteran who marries Osage woman Mollie (Lily Gladstone), and makes them pawns in his uncle William ‘King’ Hale’s (Robert De Niro) plans to kill off the Osage and claim their land and headrights. It’s a sickening chapter in American history which Scorsese treats with appropriate respect and restraint. Moments of extreme violence are punctuated by silence, the Osage people’s customs and culture are presented in exacting detail, and the escalating acts of inhumanity are depicted with a sterility that emphasises the banality of evil. Robbie Robertson’s final score is haunting, as is the film’s breathtaking finale, which – after witnessing such monstrosity and hatred – reminds us all that Scorsese may just be the most caring, conscientious, and self-aware filmmaker we have. It’s over three hours long, but Marty makes every last second count.

7) The King Of Comedy

“A guy can get anything he wants as long as he pays the price.” So goes the philosophy of Rupert Pupkin, the psychopathic protagonist of Scorsese and Robert De Niro’s fifth collaboration. Unfairly maligned on release, Marty’s bleak comedy about an aspiring stand-up comedian who goes to extreme lengths to get the attention of his favourite late night host (Jerry Lewis’ Jerry Langford) is a grimly prophetic tour-de-force. A treatise on the dangers of parasocial relationships and a character study in egoic psychosis, Scorsese slips between fantasy and reality with preternatural ease as a darkly charismatic De Niro goes through the gears, moving from a pitiful walking embarrassment to a palpable, terrifying threat. In a just world, Rupert Pupkin would be a name just as heavily featured in greatest character lists as Travis Bickle or Ray LaMotta. Something he’d be very happy about, we imagine.

6) Mean Streets

With everything we now understand a Martin Scorsese movie to be, Mean Streets is really where it all began. It’s not quite his first film — student efforts and Roger Corman quickies predate it — but as a proper industry breakthrough, the first time his cinematic voice could be truly be heard, it might as well be the starting pistol. A crackling ground-level crime drama, it established his hallmarks with considerable panache: there’s New York mobsters, small time hoodlums, Catholic guilt, explicit violence, a slow-motion character entrance to a Rolling Stones song... there’s even the now-familiar cameos from Scorsese himself (as the brilliantly-named underling Jimmy Shorts), and his beloved mother Catherine (as ‘Woman On Landing’). Perhaps most significantly, it marks the first time the filmmaker worked with Robert De Niro, cast as the feral Johnny Boy — establishing a historically important collaboration that would last decades.

5) Casino

Some critics will snipe that Casino is merely GoodFellas reheated and dressed in a gaudier suit. Well, stick that opinion in a vice and turn the crank, because despite the familiar trappings — a crime family falling apart, De Niro looking stressed, Pesci tormenting mooks, a soundtrack full of period bangers — the later film stands tall all on its own. For one thing, it’s more operatic, with its three-hour runtime, intricate web of characters, overview of how a whole city operates, and spectacular visuals (the car-bomb explosion at the start, scored to Bach’s St Matthew Passion, is maybe Scorsese’s grabbiest opening). Then there’s Sharon Stone’s fiery performance as Ginger, mesmerising from her first appearance flinging dice into the air, right through her descent into drink, drugs and depression. Despite its marathon length, the film fizzes with energy and invention, as riotously fun as Vegas itself — until the inevitably bleak sting in the tail.

4) The Wolf Of Wall Street

To date, The Wolf Of Wall Street remains Martin Scorsese’s biggest commercial hit, grossing a cool $389.8 million. It isn’t hard to see why. An outlandish, outrageous, and unapologetically excessive three-hour black-comedy biopic led by a career-best Leonardo DiCaprio, it chronicles the dramatic rise and spectacular fall of trader Jordan Belfort (DiCaprio), whose 2007 memoir gives the film its title. Easily Scorsese’s most unsubtle statement on the contemptuousness and corrupting force of capitalism in America, what makes Wolf so appealing is that, as well as being stuffed to the gills with tack-sharp sociopolitical commentary, it is just a hell of a lot of fun. Edited like an improvisational jazz solo by Thelma Schoonmaker, three hours flies by in a haze of cocaine, Quaaludes, wild parties, short-short skirts, and swanky yachts. An insatiable ensemble – Matthew McConaughey, Margot Robbie, Jonah Hill, and more – come together to tell a story of greed that makes you feel punch-drunk before spitting you out stone-cold sober. All together now! Hmm-MMM. Thump-thump. Hmm-MMM. Thump-thump…

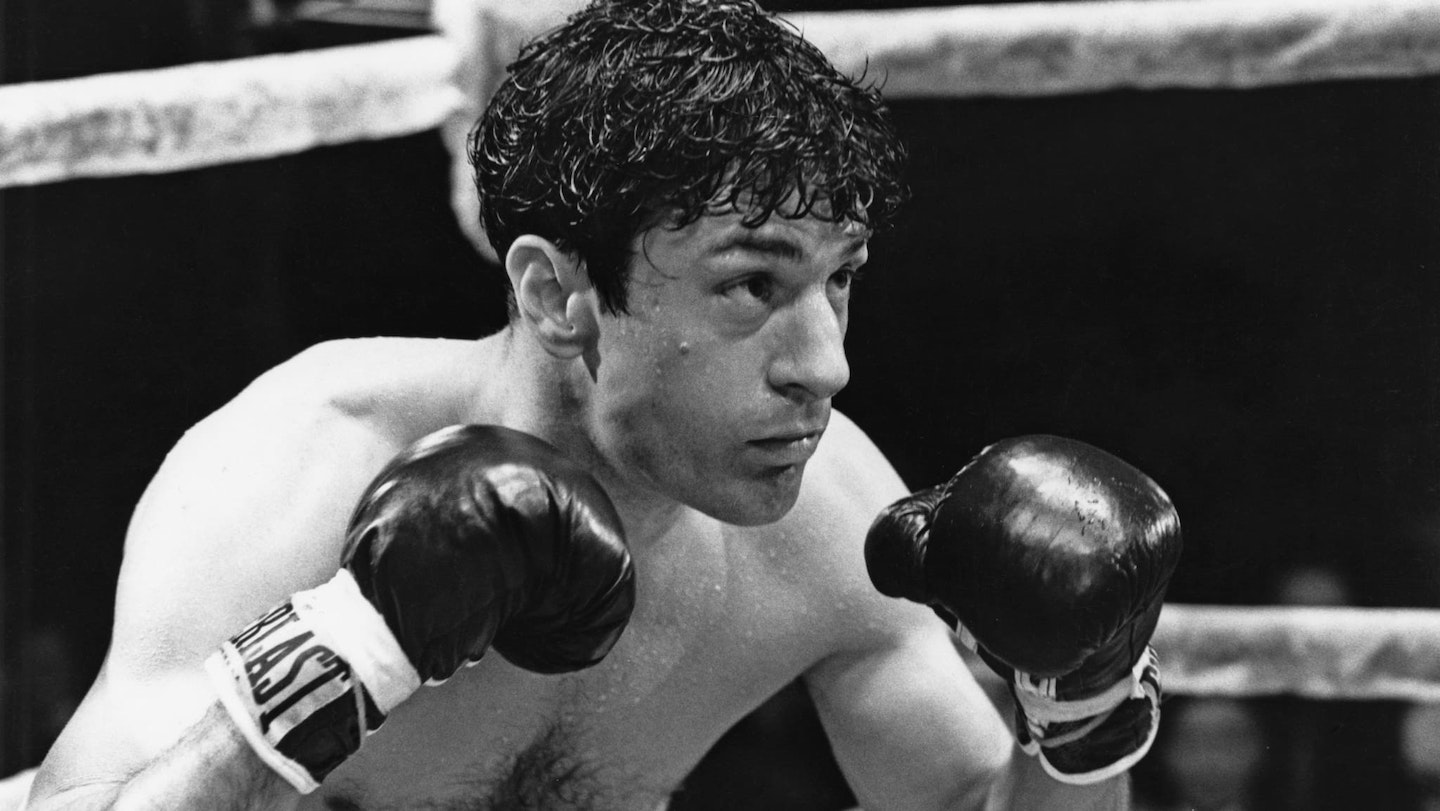

3) Raging Bull

What a sticky, uncomfortable, domestic film Raging Bull is. Is it a sports film? Is it a biopic? Yes, and yes, but also no, and no, because Robert De Niro – who generated the project – and Scorsese found exactly what they needed in the dark, murky, fuck-you heart of abusive boxer Jake LaMotta, fashioning it into a raging beast in tune with their own psychological concerns. The boxing is great, and singular – Scorsese actually fired Steadicam supremo Garrett Brown from the film because he was worried the fight scenes would be too similar to what Brown had done on Rocky (it’s okay, he later hired him for Casino). But what you remember is LaMotta’s ongoing fight with himself – his anger spilling out indiscriminately, on the street, in the bedroom, in jail. He’s an absolute alpha mess, a wretched, tortured animal of a man. Perfectly so.

2) Taxi Driver

In the intoxicating, incomparably immersive world of Scorsese’s 1976 neo-noir, smoke rises from the streets of New York city as rain falls to meet it – a perpetual process of cleansing and pollution from which none can truly escape. It’s here that Marty finds Travis Bickle, a lonely, embittered, angry insomniac lent an uncomfortably undeniable sadness and humanity by a never-better De Niro and Paul Schrader’s psychologically needling screenplay. We follow nighttime cabbie Bickle as the putrefaction he perceives in the world around him leads him down a path of violence. The famously improvised, “You talkin’ to me?” scene where Bickle rehearses his violent vigilantism is an iconic moment in a movie filled with them – but perhaps the most powerful scene of all is Travis’ phone call as he tries to get another date with Betsy. The way the camera slowly pans away to the empty corridor as a reprieve for our protagonist – his pleading too painful to watch, his loneliness abyssal – is perhaps Scorsese’s purest expression of total isolation. Almost 50 years on, its power has never been greater.

1) GoodFellas

No film hits like GoodFellas. Just like the cocaine that turns effortlessly charismatic gangster fanboy Henry Hill into a reckless maniac, that drives him to the edge of a heart attack, that makes him paranoid (OR IS HE?), the film enters your system with a jolt, giving you an immediate rush, and keeps you wanting more, more, more, MORE, until it finally comes crashing down, back to bleak reality, and then just finishes. And you have to live the rest if your life like a schnook, because, frankly, no other film compares to GoodFellas. The only solution: another big snort of GoodFellas. Scorsese, writer Nicholas Pileggi and editor Thelma Schoonmaker constructed almost the entire film like a trailer, one scene bleeding into the next, not giving you the opportunity to stop watching, to let go, to take a breath. It’s an unstoppable feat of propulsion. Now that’s cinema.